Inquiry of Applying Laban Movement Analysis to Ballroom Dance Curriculum in Higher Education

Ballroom dance has long been a form of social interaction, bringing individuals together through movement. But what if, instead of focusing solely on teaching dancers “what” to do, we emphasized “how” they engage with the dance style, their partner, and their own embodied experience?

My research explores how ballroom dance pedagogy can explore integrating Laban Movement Analysis (LMA) and somatic imagery and principles, might shift the focus from step execution to embodied exploration. By using LMA influenced imagery and language, I aim to enhance dancers' ability to sense, interpret, and respond to movement with greater awareness and adaptability. Rather than memorizing patterns, dancers can develop a deeper connection to the nuances of effort, space, weight, and flow, allowing for a more organic, responsive interaction with their partner.

What if social dancers fully immersed themselves in the moment, experiencing movement as a shared conversation rather than a prescribed sequence? How might ballroom dance transform when framed as an evolving dialogue, shaped by the dynamic interplay of physical sensation and relational awareness? By integrating somatic principles and LMA inspired language into ballroom pedagogy, I seek to cultivate a dance experience that is not only technically refined but deeply felt, one where movement is lived, and learned.

Applied Project Concept Statement

My research originates from a deep curiosity about how Laban Movement Analysis (LMA) can be applied within a ballroom dance technique class to deepen students’ engagement, understanding, and skill development. Having spent years both studying and teaching ballroom dance, I became increasingly interested in expanding my pedagogical framework beyond its traditional emphasis on foot placement, body positioning, and partner connection. While these elements remain essential to ballroom training, I was drawn to the idea that movement quality, spatial awareness, and dynamic intention could be explored more deeply using LMA inspired imagery and language. This curiosity led me to examine how integrating somatic methodologies into ballroom instruction could enrich students’ learning experiences and, more broadly, provided opportunities for ballroom dance within higher education as an embodied, research-driven practice.

Ballroom dance has historically been situated outside of the academic study of dance, often classified as a social or competitive form with codified technique. However, ballroom dancers engage with movement in complex ways, developing a refined sense of weight, momentum, and spatial negotiation through partnered interaction. Despite this, ballroom pedagogy remains largely rooted in prescriptive teaching methods that prioritize aesthetics and technical execution over kinesthetic exploration. My motivation for this research is twofold. first, to investigate how incorporating LMA concepts can provide ballroom dancers with a more nuanced understanding of movement dynamics. Second, to investigate the social dances and somatic practices within university settings by demonstrating how ballroom can benefit from, and contribute to, somatic discourse.

Methodology and Key Findings

To examine this integration, I designed my research as a qualitative, auto-ethnographic study in which I documented and analyzed my own teaching practices. By embedding LMA principles into my ballroom courses, I could observe firsthand how shifts in language, imagery, and conceptual framing influenced student learning. This methodology allowed me to move beyond theoretical speculation and engage directly with the lived experience of teaching and dancing. The practical application of this research took place in the undergraduate ballroom classes I instructed within the university and in private sectors, ranging from beginning to advanced levels. Within these courses, I deliberately replaced or supplemented conventional ballroom terminology with LMA-based descriptors. Rather than instructing students to "step forward" or "step back," I encouraged them to explore spatial intent using terms such as "advancing" and "retreating." Instead of focusing solely on frame structure, I prompted students to consider the dynamic qualities of their movement—whether they were engaging in bound or free flow, initiating movement with direct or indirect pathways, or expanding and condensing their shape in response to their partner. These subtle linguistic shifts often had visual impact on how students embodied and understood their movement, encouraging them to think beyond steps and patterns and instead consider the underlying qualities that gave their dancing expression and efficiency.

A particularly compelling aspect of this research was its influence on partner connection. Traditional ballroom pedagogy often frames leading and following as mechanical actions, relying on pressure-based cues and rigid frame structures to establish communication between partners. While these technical elements remain necessary, I sought to introduce LMA informed image strategies. For instance, when instructing leaders to "apply pressure" to initiate a turn, I have practiced applying imagery based cues such as "echoing and mirroring energy," which encouraged both partners to tune into the qualitative aspects of their movement. This approach led to notable improvements in responsiveness and adaptability, as students began to view partner work as a dynamic conversation or negotiation rather than a series of predetermined actions. Through personal journaling and class discussions, I have noticed that students have an increased ability to engage with the dancing on their own, a sense of shared responsibility in movement initiation, and a deeper appreciation for the subtleties of weight shifts and directional intent.

Implications

Throughout the course of this research, I engaged with existing scholarship in both somatics and ballroom dance pedagogy to contextualize my findings. Scholars such as Brodie and Lobel emphasize the pedagogical benefits of somatic integration in dance training, arguing that imagery based instruction enhances movement clarity, proprioception, and expressive potential. Their work encouraged my belief that ballroom dancers could benefit from a similar approach, particularly in developing a more embodied understanding of movement initiation and weight transfer. Additionally, Juliet McMains’ examination of ballroom’s aesthetic highlights the genre’s historical emphasis on external presentation over internal sensation, further encouraging my notion that LMA could offer a valuable counterbalance to existing teaching methodologies. By situating my research within these broader conversations, I approached my work not only as an investigation into ballroom pedagogy but also as a contribution to ongoing discussions about the role of somatics in dance education.

While this integration presented clear benefits for ballroom social dance students, I also encountered challenges in balancing LMA with traditional ballroom instruction. One of the primary obstacles was the students and my own resistance to new terminology. Many students, particularly those with prior ballroom experience, were accustomed to a structured language of instruction, making it a cognitive shift to introduce LMA concepts without disrupting their established learning processes. Beginning students were often unfamiliar with words such as bound flow, free flow, light weight, and strong weight. Additionally, I had to navigate the tension between ballroom’s emphasis on technical precision and an embodied exploratory of movement. Ballroom dance often prioritizes aesthetic clarity and partnership mechanics, whereas LMA invites dancers to investigate movement from an internal, kinesthetic perspective. Finding ways to bridge these approaches required intentional adaptation of the language I used to encourage that LMA principles complemented rather than conflicted with ballroom’s existing framework.

Despite these challenges, my findings emerging from this research underscored the potential of integrating somatic imagery into ballroom pedagogy. Students who engaged with imagery based instruction demonstrated increased spatial awareness, a stronger sense of musicality, and a greater ability to adapt their movement dynamics in response to their partner. Furthermore, introducing effort qualities such as weight, time, and flow encouraged dancers to explore a broader range of textures and expressive possibilities within their movement. These findings suggest that LMA is able to not only enhances technical execution but also deepens dancers’ engagement with ballroom as an embodied practice.

Looking ahead, I see this research extending beyond my personal teaching practice to contribute to broader pedagogical conversations in the field of dance education. As I develop my methodologies, I aspire to offer a unique lens for other educators interested in incorporating somatics into their own ballroom dance curricula. This includes creating this website as a digital platform where I can share and continue expanding upon my research. By making these materials accessible, I hope to support ballroom instructors in expanding their teaching approaches while also advocating for ballroom’s inclusion in academic dance programs.

Future Applications

More broadly, I view this research as part of a larger effort to bridge the gap between social dance traditions and contemporary dance scholarship. Ballroom dance, despite its technical rigor and artistic depth, has often been overlooked in higher education due to its historical association with social and competitive dance circuits. By investigating how ballroom can engage with somatic conversation and pedagogical innovation, I aim to and contribute to the ongoing evolution of ballroom dance education.

Through this process, I have come to recognize that integrating somatics into ballroom pedagogy is not simply an exercise in applying new terminology, it is a fundamental shift in how we approach ballroom training. By prioritizing movement experience thought dynamic intention, kinesthetic awareness, and emotional adaptability, this research opens new possibilities for how ballroom dancers engage with their movement and their partners. While further exploration is needed to refine these methods, the initial findings suggest that LMA offers a powerful tool for enriching ballroom education. As I continue this work, I remain committed to fostering a holistic, embodied, and research driven approach to ballroom dance, one that honors its technical foundations while embracing the depth of movement inquiry that somatics provides.

Examples and suggestions of applying somatic imagery to partnered ballroom dance

1: Standing Spin

A standing spin is a partnered movement in which the follow rotates on a single foot while maintaining a stable vertical axis. In the illustration, the dotted red line represents this axis, running from top to bottom.

The lead’s role is to support the follow by assisting in maintaining their balance or axis. Together, the lead and follow establish a connection with bound flow in their frame, flexible yet consistent, allowing for controlled resistance and yielding.

The follow initiates the spin by yielding into the frame, relying on the lead’s connection to stay balanced. Once the lead senses the follow’s readiness, they guide the rotation by responding to the momentum. The lead stabilizes and supports the follow using the frame’s connection while ensuring the follow remains centered on their axis.

During the spin, the frame and upper body connection remain in *bound flow*, while the lead’s lower body moves with *free flow*, allowing for adaptability. To exit the movement smoothly, the partnership must gradually reduce speed. Both dancers yield into the floor, redirecting their momentum downward to slow their movement, preparing for the next sequence.

Imagery examples

Axis & Rotation

"Spinning Top" Imagine the follow as a spinning top, with the central axis running straight through the body from head to toe. Just like a top, if the axis is stable, the spin remains controlled.

"Skewer through a Marshmallow" Visualize the follow as a marshmallow skewered on a stick (the axis). The body rotates smoothly around this skewer without tipping or wobbling.

Frame & Connection

"Taut, Yet Supple Rope" The connection between lead and follow is like a rope with just enough tension—neither slack nor rigid, allowing energy to travel between them.

"Tree and Vine" The lead is like a sturdy tree, providing support, while the follow moves like a vine spiraling around it. The vine (follow) needs the tree’s stability to move gracefully.

Momentum & Control

"Rolling a Coin on Its Edge" – If released smoothly, a coin rolls in a balanced way. The spin begins with controlled energy, and as it slows, it naturally leans into the floor to stop.

"Pouring Sand" When exiting the spin, imagine pouring sand from your hands—it flows downward gently rather than abruptly stopping. The dancers send their momentum into the floor similarly to slow down.

2: The Bird Lift

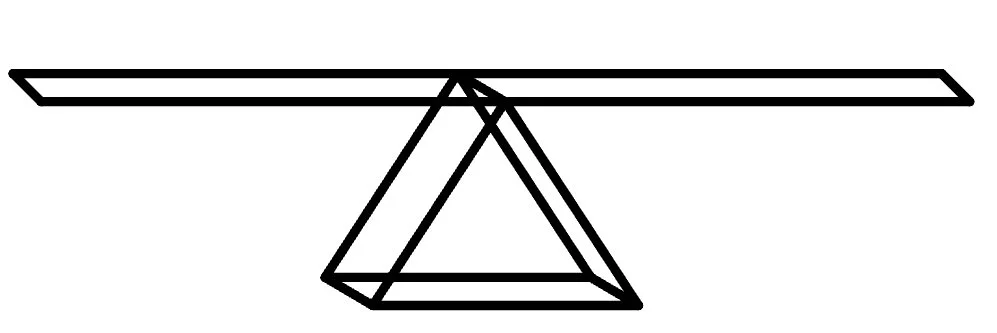

The Bird is a partnered lift in which the lead supports the follow off the ground, creating a sense of suspension and flight. The follow balances as if on a teeter-totter, with their hips serving as the fulcrum, or central balance point. Relying on a head tail connection, the follow stabilizes by engaging their core and distributing their weight evenly over the lead’s hands. The spine and back expand and grow forming a U-shaped curve in spinal extension, with the head and tail reaching toward each other along the posterior side of their kinesphere.

The lead’s role is to provide a steady base. Whether lying on their back or in another supportive position, they create a stable platform with their hands, sending energy upward through their arms, wrists, and into the follow’s pelvis. At the same time, the lead anchors themselves to the floor through yielding through their upper and lower body, deepening their relationship with gravity to provide a reliable fulcrum for the follow to balance on.

Imagery Examples

“Seesaw” Imagine that the Base is the fulcrum of a seesaw and their goal is to be a steady foundation in which the Flyer is able to balance on. Now the Flyer can imagine that they are a long board balancing on the fulcrum of the seesaw. For the Flyer and the Base more imagery is provided below to help embody the imagery for achieving this lift effectively.

Follow’s Sensation & Balance

“Floating Cloud” Imagine yourself as a cloud, effortlessly suspended in the air. There is no weight pulling you down.

"Zero Gravity" Picture being in space, where gravity has no effect on your body. You are floating, resisting any downward pull.

"Helium Balloons" Your arms and hands are as light as balloons, gently lifted away from your body rather than sinking toward the ground.

Lead’s Support & Stability

"Beam of Light" Imagine energy shooting upward from your shoulders, to your wrists, on through your wrist/palms, and into the follow’s pelvis. This imagery is to encourage a strong weight sensation in the body creating a strong support system.

"Bolted to the Ground" Visualize your body as firmly secured to the earth, unmoving and unshakable, providing a solid base for the follow.

"Twice as Heavy" Imagine your body doubling in weight, reinforcing your connection to the floor and ensuring unwavering stability for the lift.

Description of Creative Process and Methods

How I typically approach creative work?

My creative process is rooted in creative movement exploration, research, and iterative development. I approach each project with a collaborative curiosity, allowing my research interests and personal experiences to facilitate the creative movement practice. My process balances structured ideas with an openness to discovery, blending my expertise in ballroom dance, Laban Movement Analysis (LMA), and somatics.

I often like to begin by identifying a central idea or movement concept. This may stem from academic research, embodied exploration, or a response to social/cultural phenomenon. From there, I engage in movement experimentation, improvisation, and structured exercises to refine the development of the work.

What methods do I use in my creative process?

Several methods inform my process:

- Laban Movement Analysis (LMA): I use LMA to analyze movement dynamics, spatial pathways, and expressive qualities. This framework helps me make intentional choreographic choices and articulate movement in a way that enhances clarity and depth.

- Somatic Practices: Somatics allows me to explore movement from an internal perspective, emphasizing efficiency, body awareness, and movement sustainability. I incorporate these principles to develop choreography that is both expressive and functionally safe.

- Ballroom Technique: While ballroom dance is traditionally structured, I enjoy exploring ways to expand within its movement vocabulary by incorporating improvisational techniques. This approach challenges traditional partnering roles and emphasizes dynamic adaptability.

- Video Documentation and Journaling: I often document rehearsals through video analysis and reflective through personal journaling. This allows me to track movement progress, reassess choreographic choices, and refine my practices overtime.

How I incorporate feedback from peers, mentors, or students?

Feedback is an integral part of my process, but I approach it as an evolving dialogue rather than a prescriptive correction. I encourage collaborators to share insights on how movement feels in their bodies, what resonates conceptually, and where adjustments may enhance clarity or impact.

I often use structured reflection sessions where dancers and collaborators articulate their experiences, identify challenges, and suggest alternatives. This participatory approach ensures that the work remains dynamic and responsive to those involved.

What role does trial and error play in my process?

Trial and error are essential to my creative work. I view the studio as a laboratory where movement ideas are tested, refined, and sometimes discarded. By engaging in movement research and iterative exploration, I allow the work to develop organically.

At times, a movement phrase or choreographic idea may not align with the project’s intent. Rather than forcing a predetermined structure, I adapt by shifting perspectives, altering spatial configurations, or revisiting foundational research questions. This willingness to experiment ensures that the final work is both intentional and innovative.

How do you know when a creative process is complete?

I consider a work finished when the movement, concept, and performative execution align cohesively. I do not mean the process is closed; rather, it reaches a point of resolution where the ideas have been fully realized within the current creative framework. As an artists I believe no work of art is complete in the sense that it can no longer be explored. Art like a good conversation is always evolving and therefore I like to think that art has unlimited capacity for growth.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the research presented here highlights the intersection of dance, somatics, and pedagogy, specifically within the context of ballroom dance. Through my exploration of Laban Movement Analysis (LMA) and its integration into ballroom technique classes, I aim to offer a deeper understanding of how somatic practices can enhance both technical skill and personal expression. The findings not only demonstrate the potential for increased student engagement and awareness but also underscore the importance of evolving teaching methods in higher education. This research contributes to a growing conversation about the relevance of ballroom dance in academic settings, reinforcing its value as a dynamic and transformative art form. Moving forward, I remain committed to advancing both my practice and the field, fostering an environment where students can engage critically and creatively with movement.

Resources

Ballinger, D.A.,&Tremayne,P.(2005).Steps to successful performance in ballroom dance: Psychological perspectives. In T. Morris teal. (Eds), ISSP 11th World Congress of Sport

Blumenfeld-Jones, D., & Liang, S.-Y. (1970, January 1). Dance curriculum research. SpringerLink. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4020-3052-9_16

Brodie, J. A., & Lobel, E. E. (2008). Dance and Somatics: Mind-Body Principles of Teaching and Performance. McFarland & Company.

Brodie, J., & Lobel, E. (2004). Integrating fundamental principles underlying somatic practices into the dance technique class. Journal of Dance Education, 4(3), 80–87. DOI: 10.1080/15290824.2004.10387263

Dance Ltd. (1984). Dance Notation for Beginners. Dance Books Ltd 9 Cecil court London WC2.

Feltz, D. L., & Landers, D. M. (1983). The effects of mental practice on Motor Skill Learning and performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Sport Psychology, 5(1), doi. 10.1123/jsp.5.1.25

Fernandes, C. (2017). The moving researcher: Laban. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Fortin, S. (2004). Integrating the Feldenkrais Method within Dance Technique Class. Concordia University Montreal.

Frantsi, J. (2020). Focus on Mindful Movement: Problematizing Contemporary Dancers’ Training Practices Through Pilates. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 24(1), 45-58.

Green, J. (2002). Somatic knowledge: The body as content and methodology in dance education. Journal of Dance Education, 2(4), 114–118. DOI: 10.1080/15290824.2002.10387219

Haas, J. G. (2022). Dance Anatomy (4th ed.). Human Kinetics.

Hackney, P. (2002). Making Connections: Total Body Integration Through Bartenieff Fundamentals. Routledge.

Hannah Andersen (2018) Somatic, Transfer Theory, and Learning, Journal of Dance Education, 18:3, 164-175, DOI: 10.1080/15290824.2018.1409428

Harman, V. (2019). The sexual politics of ballroom dancing. Palgrave Macmillan.

Johanna. (2018). Experiencing Our Anatomy: Incorporating Human Biology into Dance Class Via Imagery, Imagination, and Somatic. Journal of Dance Education, 18(3), 215-226.

Malnig, J. (N.D.). Ballroom, boogie, Shimmy Sham, shake. Google Books.

Kearns, L. W. (2010). Somatics in action: How “I feel three-dimensional and real” improves dance education and training. Journal of Dance Education, 10(2), 35–40. DOI: 10.1080/15290824.2010.10387158

Koutedakis, Yiannis. "The Significance of Muscular Strength in Dance." Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, vol. 17, no. 1, 2013, pp. 1-6.

Lankford, D. E., Bennion, T. W., King, J., Hessing, N., Lee, L., & Heil, D. P. (n.d.). The Energy Expenditure of Recreational Ballroom Dance. International Journal of Exercise Science.

Laws, Kenneth. "The Mechanics of Dance Lifts." Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, vol. 9, no. 1, 2005, pp. 3-10.

Lee, C. (2017). Feeling and healing: Anna Halprin’s dance as healing art. Journal of Dance & Somatics Practices V9 N2.

Martha Hart Eddy (2002) Dance and somatic Inquiry in Studios and community Dance Programs, Journal of Dance Education, 2:4, 119-127, DOI: 10.1080/15290824.10387220

MacLean, J. (2016). Teachers as agents of change in curricular reform: The position of dance revisited. Sport, Education and Society, 23(6), 563–577. DOI: 10.1080/13573322.2016.1249464

Noton, E. (2019). Inspired by Dance: A Future for Kinesiology. Journal of Kinesiology Education, 12(2), 78-92.

Matsuyama, H., Aoki, S., Yonezawa, T., Hiroi, K., Kaji, K., & Kawaguchi, N. (2021). Deep learning for ballroom dance recognition: A temporal and trajectory-aware classification model with three-dimensional pose estimation and wearable sensing. IEEE Sensors Journal, 21(22), 25437–25448. DOI: 10.1109/2021.3098744

MSc, A. B. T. (2020, January 27). The use of `breath’ in Feldenkrais Method and Bartenieff fundamentals, relating to dance. DanSci Dance Studio.

The place of dance. Google Books. https://books.google.com/books?id=weYxAgAAQBAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&printsec=frontcover&pg=PP1&dq=ballroom%2Bdance%2Band%2BSomatics&hl=en&source=gb_mobile_entity&ovdme=1

Psychology: Promoting health and performance for life (CD-ROM). Sydney, Australia: Internal Society of Sport Psychology.

Tremayne, P., & Ballinger, D. A. (2008). Performance enhancement for ballroom dancers: Psychological perspectives. The Sport Psychologist, 22(1), 90–108. DOI: 10.1123/tsp.22.1.90

Vermey, R. (1994). LATIN Thinking, Sensing, and Doing in Latin American Dancing. Kastell Verlag GmbH.

Weber, R. (2018) Somatics, creativity, and choreography: Creative Cognition in Somatics-based Contemporary Dance. Unpublished PhD Thesis. Coventry: Coventry Univeristy